NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) spacecraft successfully crashed into the moon of the asteroid Didymos on September 26, in the first-ever test of a planetary defense strategy to deflect an incoming asteroid. While the test was a smashing success, the days leading up to impact were fraught with tension for NASA scientists, as they anxiously watched their spacecraft approach the asteroid.

DART scientists had help from around the world while they finalized their spacecraft’s trajectory, as astronomers everywhere raced to make observations of Didymos and pinpoint its location. But those observations could sometimes only be made from specific locations around the world, meaning international partnerships were key to making these crucial observations.

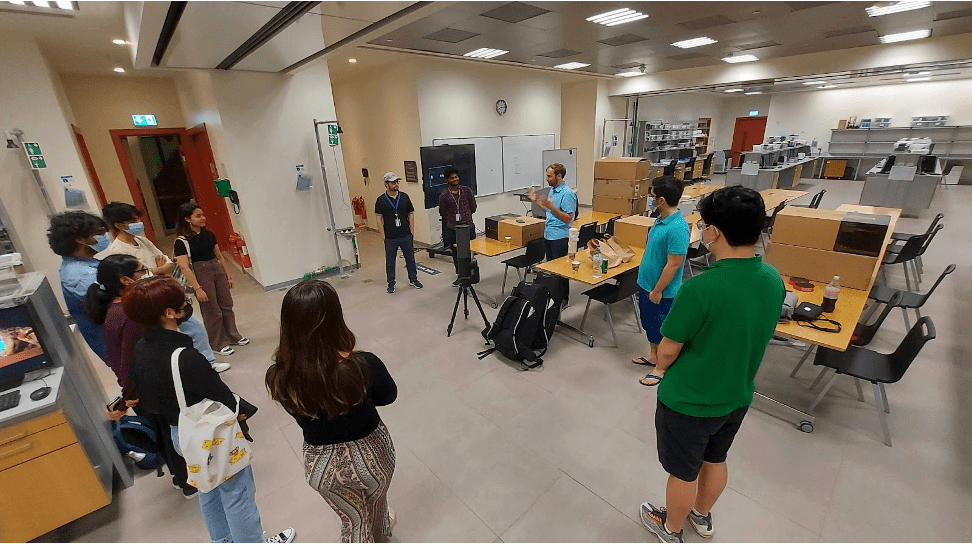

That’s why, just days before impact, Unistellar partnered with two teams of astronomers and undergraduate students from New York University in Abu Dhabi and Sultan Qaboos University in Oman, as well as astronomers from the SETI Institute, to make final observations of Didymos with their eVscopes. This international collaboration, which included the Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur and Artistotle University of Thessaloniki, was supported by the Moore Foundation.

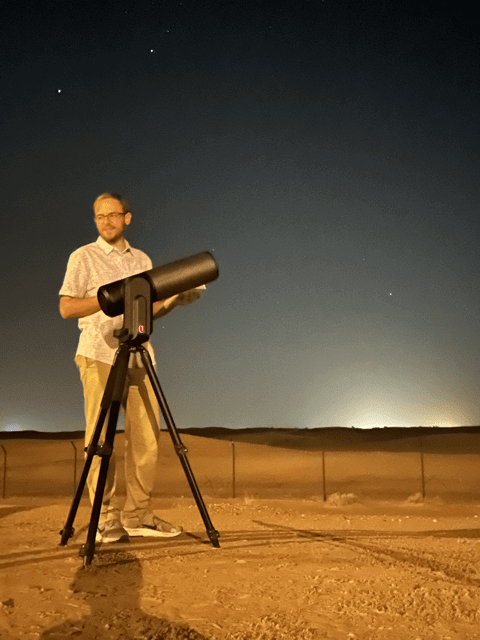

(Left) SETI Institute scientist Paul Dalba and New York University in Abu Dhabi students prepare for the occultation. (Right) The team of astronomers, students, and citizen scientists in Oman, led by SETI Institute scientist Ryan Lambert, at their observation location in the desert.

Didymos was predicted to occult, or pass in front of, a star on September 20, six days before the DART impact. But the astronomers had to meet in the middle of the desert to see it. Two teams, each led by a SETI Institute scientist, arranged 12 eVscopes precisely 500 meters (1,640 feet) apart along the predicted occultation path in the Arabian desert, where dark skies provided clear viewing. Their goal was to catch the moment when a distant star’s light was blocked by the passing asteroid, a brief glimpse that nevertheless gives scientists valuable information about an asteroid’s size, speed and orbit.

An asteroid occultation occurs when a nearby asteroid briefly blocks the light from a distant star.

It was an exciting moment for the teams, as they awaited the split second when the occultation would be visible through their Unistellar telescopes. “Asteroid occultation observations come with a surprising adrenaline rush,” says Paul Dalba, an astronomer at the SETI Institute who traveled to Abu Dhabi for the observation.

While the teams didn’t ultimately observe an occultation, that doesn’t mean the mission wasn’t a success — even a negative observation, which is not uncommon in science, is a useful one. Most of the eVscopes made confident non-detections, meaning scientists can be certain there was no occultation. These results help them hone in on where the asteroid must have been at the time of the observation.

More important was what the moment represented: People from around the world, united by astronomy, peering together through their telescopes to discover something new about the universe.

Paul Dalba preparing one of the team’s eVscopes for the occultation.

You can use your own Unistellar telescope to do the same thing! With an easy-to-use app that finds celestial targets in seconds and aims the telescope for you, it’s never been easier to contribute real data to scientific missions. You can learn more on our Citizen Science page. If you are already a Citizen Astronomer, go to our Planetary Defense Campaign page to learn how you can continue to observe Didymos post-impact.

Further readings

Unistellar Community Included In Multiple Scientific Papers

Did you know Unistellar Citizen Astronomers are often cited in published scientific papers? Find out how you can contribute too!

What Are the Names of All the Full Moons in 2024?

Discover the enchanting names of the full moons in 2024. Delve into the unique character of each lunar spectacle and embrace the allure of the night sky.

New Unistellar App Update: Version 3.0

The latest Unistellar App Update, version V3.0, is now live. Explore a smooth stargazing experience !

What to Observe This November: Open Star Clusters and More

These Halloween deep-sky objects will add some light to those dark, spooky nights. Treats, tricks, and telescopes await!

When Is the Next Solar Eclipse, and How to Observe It With a Unistellar Telescope

An annular solar eclipse is visible from the Americas on October 14. Learn how to witness the Ring of Fire with your Unistellar Telescope!

Halloween Observing Guide: Spooky Deep-Sky Objects

These Halloween deep-sky objects will add some light to those dark, spooky nights. Treats, tricks, and telescopes await!